In the experiment, capuchins were motivated to perform a task when rewarded with a slice of cucumber, until they became aware that other monkeys were being rewarded with grapes.

When the primates became aware that partners were receiving better rewards for the same task, they became agitated, threw their cucumbers at the researchers, and refused to participate in the experiment.

Humans, who we might argue are at least as intelligent (well we MIGHT), have similar reactions to injustice. Studies in employee behavior support the equity theory of motivation, showing that effort is tied to the perception that employees are being treated fair and rewards are distributed equitably and justly, based on performance. When employees perceive that they are not rewarded for their efforts compared to others, they strive to achieve justice by either doing less work, obtaining salary increases, reducing the rewards of others, or leaving these jobs entirely.

In both human and primate examples, social comparisons drive dissatisfaction. People are generally willing to put up with minimal rewards if those rewards are distributed equitably.

We would rather be collectively poor than treated unfairly.

In a recent OECD Study, the point is made that there is now widespread recognition that GDP measures or GDP per capita are misleading when it comes to understanding economic well-being.

What the study found was that household income, with a particular emphasis on income inequality was by far the truthful measure of a country's well being. It analyzed the distribution of household wealth across 28 countries, finding that wealth inequality is twice the level of income inequality on average.

The study also found that the wealthiest 10 percent of households hold 52 percent of total household wealth on average. By comparison, the 60 percent least wealthy households own little over 12 percent. The situation of inequality is worst in the United States.

In the US, the share of wealth held by the richest 10 percent of households stands at 79 percent.

The bottom 60 percent of U.S. households only hold 2.4 percent of household wealth.

This inequality gap is also wide in Europe -10 percent of households control 68 percent of wealth in the Netherlands and 64 percent in Denmark. However in both countries, there are strong government investments in social programs. For instance even the poorest citizens have access to healthcare and education.

Conversely, poor families become a liability to even the most ambitious offspring.

This effect of parental income on a child’s income, which economists call “intergenerational earnings elasticity,” or IGE, is growing in the U.S. In a comparative analysis across countries, income inequality is correlated with high IGE, and the United States has fallen behind all other Western democracies in both. The “American dream” is now more realistically the “Canadian dream.”

The truth is, despite the misguided belief; "merit" has little to do with income.

Most wealth is simply inherited.

Oh sure, you can find some people who became wealthy because of their intellectual property, or hard work, or intelligent use of their own talents...but on the Forbes list of the world's 100 wealthiest people, only a half dozen or so did not inherit their wealth.

Education is often a mechanism for the transfer of wealth, as the wealthy can send their kids to the best private schools and most expensive colleges, and use their influence to secure high paying positions afterwards. Yet, even among students at the same college, it is clear that the system favors wealthier families. Take internships, for example. In the US, the norm has been for companies and organizations to offer unpaid internships, capitalizing on the free labor of a generation desperate for the experience that has become necessary to enter the workforce. But how can a middle class or poor person afford to live while working for free? They can not.

Wealthy families can pay for their summer housing, transportation expenses and even cover tuition so the internship can count for college credit. Yet, other students must work paid retail jobs over the summer to earn money for books and other college expenses. Their resumes can not look as impressive. And what about students who want to go to law school? Students whose families can afford to pay the $1,500 fee for LSAT preparatory courses have a clear advantage over those who cannot. These are but a few examples.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in the Janus case surprised no one who pays attention to America’s highest judicial panel. Every analyst following the case expected the Supremes to rule against America’s public sector unions. And by a 5-4 margin, they did.

The impact from this decision? The Supreme Court’s decision in Janus will make the United States still more unequal.

The five justices who decided Janus never, of course, mentioned anything about inequality in their ruling that public sector unions cannot collect representational fees from the nonmembers they are legally required to represent. The Janus majority justices talked instead about protecting First Amendment rights. But that lofty philosophizing merely served as a convenient cover for the continuing assault on the basic human right to justice on the job.

This assault was an effort bankrolled over the years by a relentless gang of fiercely anti-union deep pockets and it has been remarkably effective.

Back in the 1950s, over a third of America’s workers belonged to unions.

And that statistic underplayed the actual extent of the nation’s trade union presence.

In the private sector, outside the South, unions represented over half the workforce in the decades after World War II.

The workers unions didn’t represent in those years directly benefited as well from heavy trade union “density.” Nonunion employers simply couldn’t hire and keep workers unless they improved what they had to offer in pay and benefits.

The business pushback against union influence started picking up considerable momentum in the 1970s, then achieved critical mass in the 1980s with Ronald Reagan in the White House.

In 1981, Reagan fired and permanently replaced striking air traffic controllers.

Two major private sector employers, Phelps Dodge and International Paper, would soon follow Reagan’s example with their own striking unions. Other employers took notes.

This willingness to replace striking workers, historian Joseph McCartin has written, would reshape “the world of the modern workplace.” Strikes would now almost totally disappear from American labor relations. Strikes had given workers leverage. Without them, unions simply couldn’t effectively pressure employers to increase wages as productivity & profits grew.

Other assaults on worker rights aggravated labor’s growing marginality in America’s workplaces.

The nation’s labor laws — statutes meant to protect workers’ right to bargain collectively with their employer — were killed.

Employers who violated these statutes no longer faced any significant liability.

The assaults took a toll. By 1983, union membership had dropped to 20.1 percent of America’s nonsupervisory workforce. In 2017, the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics reported only 10.7 percent of the nation’s employees carried union cards.

And these stats overplay the actual extent — in the private sector — of the trade union presence in 21st-century American life. In the mid-20th century, most all union members worked in the private sector. Today union members make up 34.4 percent of the public sector workforce and only 6.5 percent of workers in the private sector.

Nine states now have overall union member rates under 5 percent. In other words, over vast swatches of the American economic landscape, unions barely exist at all.

What does exist in the United States today?

A level of income and wealth inequality not seen since the 1920s, another era of minimal union influence. The history of America’s past century paints a vividly clear picture: Inequality in America has increased in the years when unions have been at their weakest and decreased in the years when unions have been at their strongest.

For years, the conventional economic wisdom has blamed our contemporary extreme inequality on irreversible trends like advancing technologies and globalization. But this myth is no longer defended by mainstream economists. Recent mainstream research has emphasized how crucial a role union density plays in income and wealth distribution.

Researchers from the International Monetary Fund (of all places!) have examined the economic experiences of 20 developed nations between 1980 and 2010. Most all of these nations showed a declining union presence over the course of these years, with that decline severe in some nations — like the United States — and much less severe in others. What they found was declining union density was “strongly associated” with the growing share of national income going, within each nation, to the richest 10 percent of the population. “The decline in union density,” this IMF research indicates, “explains about 40 percent of the average increase in the top 10 percent of income share in our sample countries.”

Part of that growing income share of the already affluent reflects the lower wages of workers in nonunion workplaces. The de-unionization that “weakens earnings of middle- and low-income workers,” the IMF researchers explain, “necessarily increases” the income share of corporate executives and shareholders.

Another part of that growing top 10 percent income hoarding reflects the loss of influence over basic public policy decisions that average wage earners wielded when unions were stronger.

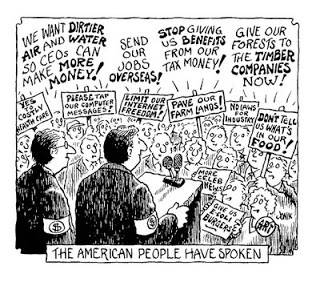

That shrinking influence leaves the wealthiest 10% in control of the the economic and political system, and they rig it in their favor.

Other global economic bodies — like the OECD, the official economic research agency of the developed world — have concluded that our current high levels of inequality do no society any good.

“By not addressing inequality,” OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría has pronounced, “governments are cutting into the social fabric of their countries and hurting their long-term economic growth.”

Last year, trade union leaders from around the world descended on an OECD Ministerial Council Meeting in Paris to make the case that significant progress against inequality will only come when workers have the bargaining power to “benefit from structural and technological change.” along with the

The U.S. Supreme Court has totally ignored economic reality with its Janus decision.

Come to think of it, the U.S. government in it's efforts to appease the billionaire class since the 1980s, has ignored economic reality entirely.

As for the rest of us?

Unlike the SCOTUS...or the other branches of government...

We can’t afford to.

Postscript:

The Rich do not always win...remember that.

The memory of the triumph over plutocracy that created the American middle class must not be permitted to be extinguished. The future may appear to be bleak, and if we do not change the course we are on, it will be. However that is a matter of choice. We need not choose a bleak future.

We must not let others convince us there is no choice.

Recommended reading on the subject:

an analysis of how America went from a plutocracy to a more egalitarian society and back again.

This inequality gap is also wide in Europe -10 percent of households control 68 percent of wealth in the Netherlands and 64 percent in Denmark. However in both countries, there are strong government investments in social programs. For instance even the poorest citizens have access to healthcare and education.

The United States leads the world in wealth inequality.

Inequality justified by performance isn't a problem. But the idea that one can get ahead and achieve based solely on merit has become difficult to defend. Research from the Brookings Institution shows there is some minor opportunity for economic mobility at the middle of the economic ladder. (Middle-income kids have some opportunities to shape their own destinies, moving up or down in socioeconomic status) Yet the middle class is shrinking. It grows smaller every day.

Those born to wealthy parents stay wealthy, and those born to poor parents stay poor.

Wealthy families provide ample safety nets that allow their children to succeed, quite often despite very poor choices , little effort, and even behavior that; had they been born to a less wealthy parent, would have landed them in jail. Conversely, poor families become a liability to even the most ambitious offspring.

This effect of parental income on a child’s income, which economists call “intergenerational earnings elasticity,” or IGE, is growing in the U.S. In a comparative analysis across countries, income inequality is correlated with high IGE, and the United States has fallen behind all other Western democracies in both. The “American dream” is now more realistically the “Canadian dream.”

The truth is, despite the misguided belief; "merit" has little to do with income.

Most wealth is simply inherited.

Oh sure, you can find some people who became wealthy because of their intellectual property, or hard work, or intelligent use of their own talents...but on the Forbes list of the world's 100 wealthiest people, only a half dozen or so did not inherit their wealth.

Education is often a mechanism for the transfer of wealth, as the wealthy can send their kids to the best private schools and most expensive colleges, and use their influence to secure high paying positions afterwards. Yet, even among students at the same college, it is clear that the system favors wealthier families. Take internships, for example. In the US, the norm has been for companies and organizations to offer unpaid internships, capitalizing on the free labor of a generation desperate for the experience that has become necessary to enter the workforce. But how can a middle class or poor person afford to live while working for free? They can not.

Wealthy families can pay for their summer housing, transportation expenses and even cover tuition so the internship can count for college credit. Yet, other students must work paid retail jobs over the summer to earn money for books and other college expenses. Their resumes can not look as impressive. And what about students who want to go to law school? Students whose families can afford to pay the $1,500 fee for LSAT preparatory courses have a clear advantage over those who cannot. These are but a few examples.

The impact from this decision? The Supreme Court’s decision in Janus will make the United States still more unequal.

The five justices who decided Janus never, of course, mentioned anything about inequality in their ruling that public sector unions cannot collect representational fees from the nonmembers they are legally required to represent. The Janus majority justices talked instead about protecting First Amendment rights. But that lofty philosophizing merely served as a convenient cover for the continuing assault on the basic human right to justice on the job.

This assault was an effort bankrolled over the years by a relentless gang of fiercely anti-union deep pockets and it has been remarkably effective.

Back in the 1950s, over a third of America’s workers belonged to unions.

And that statistic underplayed the actual extent of the nation’s trade union presence.

In the private sector, outside the South, unions represented over half the workforce in the decades after World War II.

The workers unions didn’t represent in those years directly benefited as well from heavy trade union “density.” Nonunion employers simply couldn’t hire and keep workers unless they improved what they had to offer in pay and benefits.

The business pushback against union influence started picking up considerable momentum in the 1970s, then achieved critical mass in the 1980s with Ronald Reagan in the White House.

In 1981, Reagan fired and permanently replaced striking air traffic controllers.

Two major private sector employers, Phelps Dodge and International Paper, would soon follow Reagan’s example with their own striking unions. Other employers took notes.

This willingness to replace striking workers, historian Joseph McCartin has written, would reshape “the world of the modern workplace.” Strikes would now almost totally disappear from American labor relations. Strikes had given workers leverage. Without them, unions simply couldn’t effectively pressure employers to increase wages as productivity & profits grew.

Other assaults on worker rights aggravated labor’s growing marginality in America’s workplaces.

The nation’s labor laws — statutes meant to protect workers’ right to bargain collectively with their employer — were killed.

Employers who violated these statutes no longer faced any significant liability.

The assaults took a toll. By 1983, union membership had dropped to 20.1 percent of America’s nonsupervisory workforce. In 2017, the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics reported only 10.7 percent of the nation’s employees carried union cards.

And these stats overplay the actual extent — in the private sector — of the trade union presence in 21st-century American life. In the mid-20th century, most all union members worked in the private sector. Today union members make up 34.4 percent of the public sector workforce and only 6.5 percent of workers in the private sector.

Nine states now have overall union member rates under 5 percent. In other words, over vast swatches of the American economic landscape, unions barely exist at all.

A level of income and wealth inequality not seen since the 1920s, another era of minimal union influence. The history of America’s past century paints a vividly clear picture: Inequality in America has increased in the years when unions have been at their weakest and decreased in the years when unions have been at their strongest.

For years, the conventional economic wisdom has blamed our contemporary extreme inequality on irreversible trends like advancing technologies and globalization. But this myth is no longer defended by mainstream economists. Recent mainstream research has emphasized how crucial a role union density plays in income and wealth distribution.

Researchers from the International Monetary Fund (of all places!) have examined the economic experiences of 20 developed nations between 1980 and 2010. Most all of these nations showed a declining union presence over the course of these years, with that decline severe in some nations — like the United States — and much less severe in others. What they found was declining union density was “strongly associated” with the growing share of national income going, within each nation, to the richest 10 percent of the population. “The decline in union density,” this IMF research indicates, “explains about 40 percent of the average increase in the top 10 percent of income share in our sample countries.”

Part of that growing income share of the already affluent reflects the lower wages of workers in nonunion workplaces. The de-unionization that “weakens earnings of middle- and low-income workers,” the IMF researchers explain, “necessarily increases” the income share of corporate executives and shareholders.

Another part of that growing top 10 percent income hoarding reflects the loss of influence over basic public policy decisions that average wage earners wielded when unions were stronger.

That shrinking influence leaves the wealthiest 10% in control of the the economic and political system, and they rig it in their favor.

Other global economic bodies — like the OECD, the official economic research agency of the developed world — have concluded that our current high levels of inequality do no society any good.

“By not addressing inequality,” OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría has pronounced, “governments are cutting into the social fabric of their countries and hurting their long-term economic growth.”

Last year, trade union leaders from around the world descended on an OECD Ministerial Council Meeting in Paris to make the case that significant progress against inequality will only come when workers have the bargaining power to “benefit from structural and technological change.” along with the

The U.S. Supreme Court has totally ignored economic reality with its Janus decision.

Come to think of it, the U.S. government in it's efforts to appease the billionaire class since the 1980s, has ignored economic reality entirely.

As for the rest of us?

Unlike the SCOTUS...or the other branches of government...

We can’t afford to.

The Rich do not always win...remember that.

The memory of the triumph over plutocracy that created the American middle class must not be permitted to be extinguished. The future may appear to be bleak, and if we do not change the course we are on, it will be. However that is a matter of choice. We need not choose a bleak future.

We must not let others convince us there is no choice.

Recommended reading on the subject:

an analysis of how America went from a plutocracy to a more egalitarian society and back again.